Prophecy and parenthood have little in common at first glance. But on closer examination, both require you to let go of the belief that you are in control of anything.

And both are about hope.

Pregnancy and parenthood are a really good way to discover that you are not in control. Of anything. Of course, this is a lesson that we all have to learn sooner or later, but the path of parenthood certainly teaches it quickly. Just the circumstances of Mary’s and Elizabeth’s pregnancies are a perfect example. For some, like Elizabeth,  the struggle to become pregnant is a lifelong ordeal, while others, like Mary, find themselves unexpectedly expecting.

the struggle to become pregnant is a lifelong ordeal, while others, like Mary, find themselves unexpectedly expecting.

And then, once pregnant, the planning begins. These days, there are birth plans and announcements and gender-reveal parties and scheduled c-sections or inductions to accommodate the doctor’s schedules, all based on the basic idea that we can, somehow, be in control of this whole affair.

But all of that planning is just a delusion. I went into labor with Grace 5 weeks early, but even before that, I had begun to come to terms with how little control I had over this pregnancy and childbirth thing. Gestational diabetes and hypertension put an end to my idealistic plans for a home birth or a new age-y Seattle-Style birthing center. It was a hospital birth – no midwife would consider anything else. Then, when I went into labor 5 weeks early, there was no further pretense of planning. This baby was arriving whether we were ready or not. And we were not. No bag packed, no freezer full of food, nothing ready.

It was a crash course in how little control we had, a course that continues to this day and only grows more obvious with each additional kid. Holden arrived on the day of his baby shower, so that we had to tape a note to the door for our guests, who arrived at our house 3 hours after he had arrived at the hospital.

And, of course, it was not part of my long-term plan to be ordained at 7 months pregnant, but Elinor had other ideas. She decided to get her first semester of Greek in utero and accompanied me into my first 6 weeks of ministry here at Peace.

But alongside this growing awareness that you have no control over, well, anything, this new life brings with it a sense of absolutely irrational purpose, promise, and hope. Even as the sense of our own inadequacy grows in the face of this immense responsibility, so does the feeling that this little life could be amazing, that because of this tiny human, who has now become a medium sized or even full-grown human, the world could become a better place. Has already become a better place.

And that’s the other link between prophecy and parenthood: both lean into hope – the hope that something amazing and new and wonderful is brewing.

This is what sends Mary with haste to the Judean hill country.

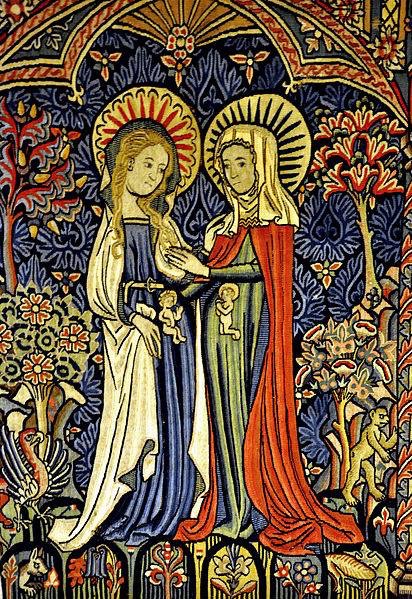

This is what brings these two pregnant women, unexpectedly expectant, together to share their thrilling expectations, to share their words of prophecy and proclamation.

Elizabeth is an old woman by the time this story takes place. Like her ancestors Sarah and Hannah, she has long since given up hope of becoming a mother when she discovers that she is pregnant. A pregnancy she had once longed for but no longer expected. She had come to accept a long time ago that she was not in control. And now, she is in her sixth month of pregnancy and here comes her kinswoman Mary.

Mary is so young, so full of promise, promise now seemingly ruined. Because at this time, in this place, what can become of a young woman pregnant out of wedlock, unexpectedly expecting, likely to face shaming and rejection for her pregnancy, shaming and rejection that Elizabeth herself had once faced for her own lack of pregnancy. Women’s bodies have ever been subjected to the hopes and expectations of their society, and when they fail to live up to those hopes and expectations, society demands a punishment.

But in this story the shaming and rejection never come. Instead of being the vessels of society’s demands, these two women’s bodies have become the vessels of the world’s hope, of God’s promises. They have been made into living prophecies, the proclamation that God is present and active in this world.

Prophecy in Scripture is not quite the same thing as it is in popular culture. In the movies and TV, our popular imagination always make prophecy about some prediction of future calamity or good, along with a series of signs that we can use to determine when the prophecy is going to happen.

But Biblical prophecy is different. Biblical prophecy, like parenthood,is about control and hope. When a prophet speaks in the Bible it is most often to remind us that we are not in control, or to point us toward the hope of the future. The prophets always speak uncomfortable truths.

Sometimes they are reminding those in power of their responsibility for the poor, the widows, and the orphans.

Sometimes they are scolding the people for neglecting the aliens, the foreigners who have come to them for help and shelter.

Sometimes they are pointing out the abuses of the wealthy and the religious authorities.

But always what they come back to is the reminder – you are not in control. God is.

You may think that you are the one in charge, and you may be abusing that power, but at the end of the day, God is the king. Your administration is only a temporary thing. God’s reign is forever.

For the powerful and the wealthy and the insiders, this is not good news. Because it turns out that God’s administration has different priorities, and God’s priorities almost always take power and wealth and insider status away from those who abuse it.

But even as they are speaking these uncomfortable truths, the prophets of the Bible are also delivering hope and speaking words of promise.

Because if you are poor, a widow, an orphan, an alien at the door, an outsider, an asylum-seeker, a beggar, oppressed, imprisoned, afflicted in any way, God’s priorities bring hope.

For these people, the prophets speak of new life, of a world in which all have enough and everyone is accepted as they are, and the flocks are fed.

The prophets promise that the mighty will cast down from their thrones while the lowly are lifted up, that the hungry will be fed and the proud will be scattered.

The prophets promise that God’s lovingkindness, that God’s steadfast mercy and love, will have the last word.

In the Book of Luke, the Messiah who has arrived in Jesus Christ is first and foremost a prophet.

As I said on the first Sunday of Advent, in Christ, God comes to us in History, in Mystery, and in Majesty. And in the four Gospel accounts, the authors each emphasize a different one of these, although all three can be found in each. Sometimes the Messiah is a King, coming in Majesty to set human thrones aside. Sometimes the Messiah is a Savior, coming in Mystery to forgive sins and defeat death.

But for Luke, who begins his book as “an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us,” the focus is primarily on History. And so the Messiah is a Prophet, come to remind us of God’s presence, of God’s activity, of how God turns human history into God’s story.

And so Luke begins with pregnancies and parents and prophets. These pregnancies themselves, like all pregnancies everywhere to some extent, are embodied prophecies, living instances of hope and promise. A barren woman unexpectedly expecting well past her years of motherhood. A young virgin impossibly expecting by the grace of God. These events themselves are so telling that no words are necessary, and in fact, Elizabeth’s husband Zechariah is silenced by the angel Gabriel, as if to remind him and us that God’s work does not require our interpretation and manipulation, our planning and our perfecting. God is at work and God is in control, and our plans and priorities will take a back seat. If parenthood in his old age won’t convince Zechariah of this, maybe 9 months of silence will. It is only after Mary’s song, after Elizabeth gives birth, after John is named, that Zechariah’s silence ends and he breaks forth with his own song, declaring that God’s plans are good enough for him.

Meanwhile, Mary receives the angel Gabriel with the open guileless trusting hope of the young, simply saying, “Let it be.” For this trust, Elizabeth declares, Mary will be praised throughout the ages, blessed throughout the world, and has the embodiment of hope already growing inside her.

These babies, John and Jesus, will both grow, as babies do, and become something amazing. They will surpass their parents’ expectations, and they will bring grief to the women who carried them. These women, who stand here today with hope and joy on their lips will someday witness the brutal death of these children at the hands of corrupt and violent regimes. And again, their prophetic lives will bear witness to the harsh truths of human power, abused and misused for power’s sake.

But here at the beginning of Luke, it is all about the God who shows up in history, who comes with words and deeds of prophecy, whose very birth is itself prophetic, showing us that God can and will come to us where and when we least expect it. We are not in control, and we encounter that truth in our daily lives, through the unexpected ways that God shows up. Through the joy we inexplicably receive when we give of ourselves, when we share what we have, when we become for someone else the embodiment of hope.

So Mary sings what her body lives, and Zechariah echoes her song at the birth of John, and Simeon in a couple weeks will sing his prophecies as well, on encountering the baby Jesus in the Temple. And all these songs, all these births, and even their ultimate deaths, tell us the truths that the prophets have sung for centuries:

God is in control, and God’s priorities are not ours.

And though we will try to manipulate and interpret, to make our own plans and bring our own power to bear, to make history reflect human priorities, though we will build higher walls and rehearse the stories of insider privilege, and though we will place tyrants on thrones and think proud thoughts and hoard wealth and neglect the widows and orphans and aliens who turn to us for help, God is busy coming into this world, being born in every time and place, bringing God’s unexpected mercy and God’s steadfast love into being

Mary is the embodiment of God’s already and not yet, a continuation of the long line of God’s prophets. Mary’s song, sung in the past tense, is about the God who has always been up to this exact thing. Always been coming to God’s people and blessing them, down through the ages, always giving the hope that comes with new life.

And Mary’s body, Mary’s very being as the Mother of God, is about the God who is always going to come to us, always looking to be born into this world, to embody the hope and blessing, the assurance that we are in fact not in control, and this is indeed good news.